BART’s Doomsday Gambit: Pay Up or Lose Your Station

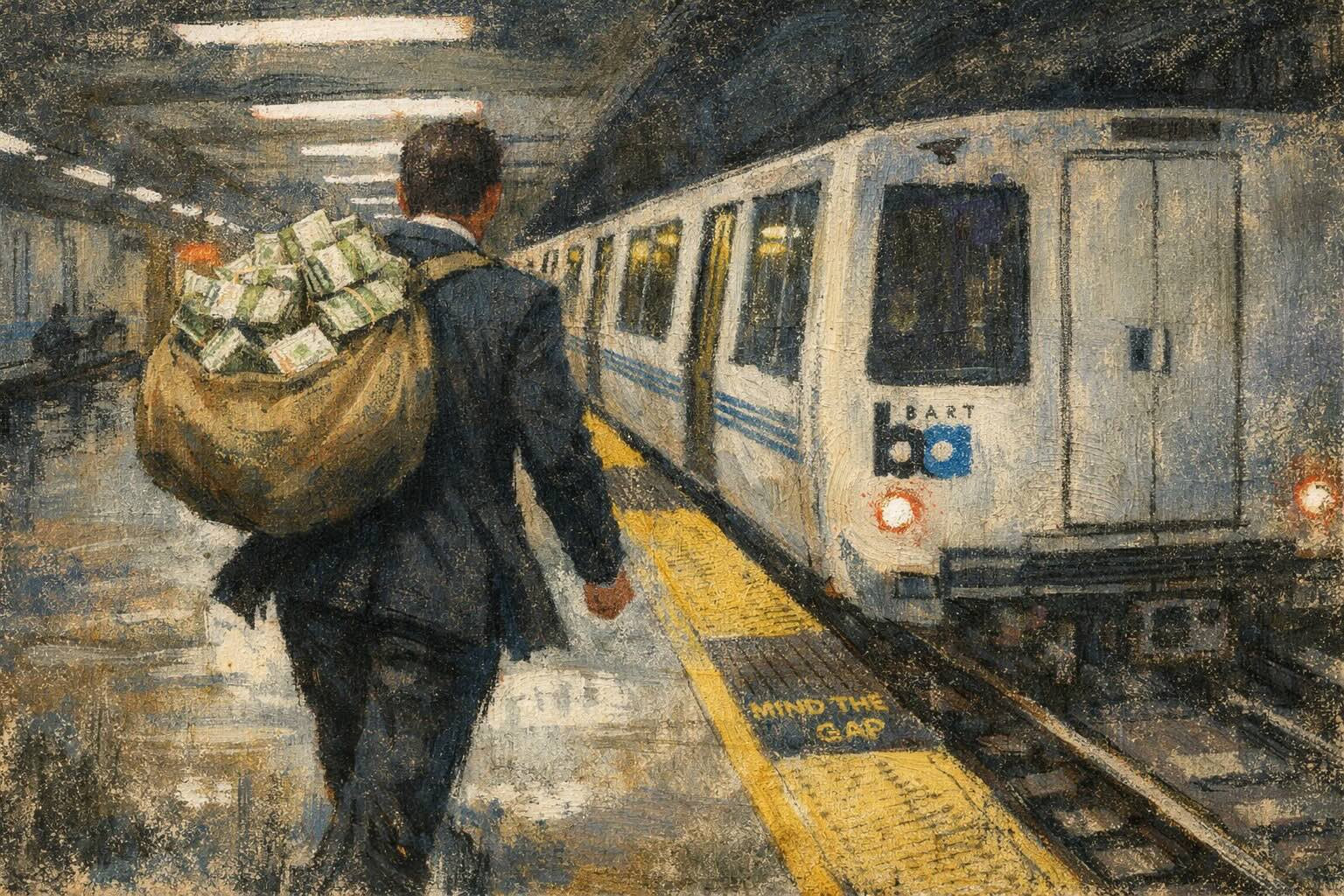

Instead of fixing endemic graft, overtime abuse, and union-protected waste, they’re holding your commute hostage for a November tax bailout.

This is the threat: pay up or watch stations close. But what we should really do is demand accountability before paying up.

This is the threat: pay up or watch stations close. But what we should really do is demand accountability before paying up.

TL;DR

BART threatens to close 10+ stations unless voters approve new taxes—while janitors earn $271,000 hiding in closets, 57 employees double their salaries through overtime, and the Inspector General gets obstructed for investigating.

I grew up taking BART. As a working class kid taking BART from my home in Fremont to UC Berkeley for my first CS classes, or to San Francisco to work at my first coding job, I think fondly of it. I want BART not just preserved but expanded! More lines, more frequency, more late-night service. But that requires fixing governance first, and that’s not what we’re seeing today.

Instead of addressing endemic incompetence, graft, and crime, BART is threatening to shut down stations in order to extort more taxes. That’s not fiscal necessity—it’s a shakedown.

Archived tweetInstead of addressing endemic incompetence, graft, and crime, @SFBART is threatening to shut down stations in order to extort more taxes. https://t.co/aedxH9fgNO

Kane 謝凱堯 @kane February 06, 2026

The transit agency staring down a $400 million annual deficit isn’t asking voters to help fix a broken system. They’re demanding a ransom: approve a half-cent to one-cent regional sales tax in November, or watch ten stations go dark as early as January 2027.

The Threat: Close Stations or Pay Up

The Chronicle reports that BART has identified ten stations for closure under its “phase one” doomsday scenario—Pittsburg Center, North Concord, Orinda, South San Francisco, San Bruno, Castro Valley, West Dublin/Pleasanton, South Hayward, Warm Springs, and the Oakland Airport connector. That’s half the yellow line gutted. Phase two would add five more, including Colma, Millbrae, Dublin/Pleasanton, Pittsburg/Bay Point, and Antioch. The blue line would die entirely.

The remaining stations wouldn’t just lose neighbors—they’d lose hours. Service would end at 9 PM every night, killing transit for swing-shift workers, night students, and anyone who wants a beer without worrying about driving home. Trains would run every 30 minutes instead of 20.

But here’s what you won’t hear from BART spokespeople, or the many people who are trying to rally more money for transit when we haven’t taken care of basic accountability first. BART eviscerated its own finances long before any ballot measure failed. The doomsday scenario isn’t a consequence of underfunding. It’s the inevitable result of decades of mismanagement that BART refuses to fix—and now wants you to subsidize.

The $80 Million Overtime Grift

BART spent $96 million on overtime in 2023. That’s 14% of the entire agency’s spend on salaries—not on new trains, not on security, not on cleaning up the stations that smell like an open sewer. On overtime.

A KQED investigation found that 57 employees more than doubled their base salaries through extra hours. The Inspector General blamed rigid union rules, persistent staffing gaps, and an outdated timekeeping system so broken that investigators couldn’t even extract the data they needed. When IG Claudette Biemeret told the board she couldn’t access overtime justification codes, Chief Financial Officer Joseph Beach contradicted her in the same meeting, claiming the data was accessible all along.

When SEIU 1021 President John Arantes testified about the audit, he didn’t address the findings. He called them “totally slanderous” and demanded higher wages so workers wouldn’t “need” to work overtime. That’s the mentality running BART: more money is always the answer, accountability is always an attack.

The Janitor in the Closet

The overtime culture isn’t abstract—it’s embodied in specific, almost unbelievable stories. In 2015, BART janitor Liang Zhao Zhang earned $271,000 on a base salary of $57,945. He claimed to work an average of 114 hours per week—nearly three times a full-time schedule.

When KTVU pulled security footage, they found Zhang disappearing into a storage closet for hours at a time. BART’s response? Officials told reporters Zhang “legitimately earned his pay by working long and hard.”

Forty-nine other BART janitors earned more than $100,000 that year. BART confirmed no auditing had been conducted. The agency briefly tamped down overtime for custodial staff after the public outcry—then quietly let it creep back up. By 2018, a station agent was claiming to have worked 361 days in a single year.

The Ghost Station Paychecks

In 2016 and 2017, BART paid eight employees to staff the Warm Springs/South Fremont station for seven months—before it opened. No trains. No riders. Just paychecks going out the door to people showing up to a non-functioning facility because construction delays kept pushing back opening day.

The Independent Institute documented the absurdity: nobody thought to stop cutting checks while the station sat empty. This is what happens when an organization treats public money as an entitlement rather than a responsibility.

The 2013 Strike Template

To understand why BART refuses to touch labor costs, go back to 2013. Workers already among the highest-paid transit employees in the nation demanded a 23.5% wage increase. They were paying $92 per month for health insurance—the national average was $360. They contributed nothing to their pensions.

BART workers staged two disruptive strikes that shut down Bay Area commutes. The agency caved, granting raises of more than 15% over four years in exchange for token pension contributions. Those contracts haven’t been renegotiated since—they’re still in place today, a decade after ridership began its collapse.

The 2013 strikes set the template: when unions threaten to cripple service, BART leadership surrenders and goes to the public for more money. The current crisis isn’t an accident. It’s what you get when you lock in gold-plated contracts and then watch your customer base evaporate.

The Fare Revenue Death Spiral

BART’s own financial reports expose how upside-down the business model has become. In FY2024, fare revenue was roughly $219 million. Operating expenses were about $1.02 billion. The agency’s annual report shows that employee-related costs—wages, benefits, overtime—dwarf what riders pay to use the system.

Before the pandemic, fares covered about two-thirds of operating costs. Today, they cover less than a quarter. Over the past decade, BART ridership has fallen by more than 50%, while employee headcount rose by almost 30% and total employee spending nearly doubled. That’s the trajectory that produced the “fiscal cliff.”

The agency didn’t adapt to declining ridership by cutting costs. It assumed taxpayers would always cover the gap.

The Inspector General They Drove Out

When someone tried to investigate, BART drove them out. Inspector General Harriet Richardson resigned in 2023, accusing top leaders of repeatedly impeding her watchdog role. She cited a pattern of obstruction from staff and major unions—a finding the Alameda County grand jury later confirmed.

State Senator Steve Glazer tried to pass legislation strengthening the IG’s powers. Governor Newsom vetoed it at BART’s behest. The message was clear: accountability is the enemy.

The current IG, Claudette Biemeret, ran into the same walls. Her overtime audit couldn’t even access basic timekeeping data. When she asked for overtime justification codes, she was told the information was inaccessible—until the CFO contradicted that claim publicly.

The Time Theft Ring

It gets worse. Multiple BART employees have been caught running time theft schemes—clocking in for work and then going home or running personal errands while collecting full pay.

The SF Standard reported that one technician falsely billed over $9,000 in wages across 18 days in 2023. He earned $253,000 in total compensation in 2022—147% above his base salary. The San Mateo County DA filed felony charges. An outstanding arrest warrant has been issued.

The Inspector General has substantiated five time theft allegations with the same pattern in two years. One employee earned $341,000—nearly triple his base salary—while spending most shifts away from work. His manager may have been complicit.

The Subsidy Death Spiral

Here’s the conceptual frame that explains all of this: once a transit agency learns it can paper over bad performance with subsidies, it stops optimizing for riders and starts optimizing for politicians.

Analysts at the Independent Institute have documented the pattern. BART had a strong farebox recovery ratio before the pandemic. Crime, grime, and reliability problems were already mounting, but the agency didn’t reform—it assumed Sacramento would bail them out. After COVID cratered ridership, BART leaned even harder into that assumption instead of using the crisis to fix contracts, clean stations, and attack crime.

The result is a classic death spiral: service quality declines, paying riders leave, revenue shrinks, the agency cries poverty, demands more taxes, and the cycle repeats—each time with fewer riders and higher subsidies.

BART Board Director Debora Allen has called this out publicly: “BART management appears uninterested in addressing monumental operating deficits.” She’s right. A coalition of labor-dominated board members, executive management, unions, and transit activists benefits from perpetual crisis. Reform would threaten their arrangement.

The Crime-Fare Evasion Connection

Here’s a stat BART doesn’t advertise: 80% of those arrested for crimes on the system had not paid a fare. Fare evasion isn’t a victimless technical violation—it’s the gateway crime that invites worse behavior. Let it slide, and you’re signaling that the rules don’t apply.

Surveys show most riders are unhappy with fare enforcement. Director Allen has said the public is “speaking very loud” about the lack of enforcement. But BART’s board actually opposed a bill that would have maintained criminal penalties for fare evasion. The priorities are inverted.

The Proof: Safety Brings Riders Back

Here’s the data that destroys BART’s case for a bailout without reform: crime dropped 41% in 2025. Violent crime fell 31%. Property crime dropped 43%. Robberies decreased 60%. Auto thefts were cut in half.

During that same period, BART delivered nearly 5 million more trips than in 2024. Crime plummeted and ridership rose—because BART finally invested in visible safety: more officers on trains, more ambassadors and inspectors, and 715 new taller fare gates at all 50 stations completed four months ahead of schedule.

Make BART safe and the riders will return. It’s not complicated. But it does require BART to turn away from grifting and luxury beliefs.

The Hong Kong Model

It doesn’t have to be this way. Hong Kong and Tokyo have private for-profit subway systems that are clean, safe, reliable, with near-perfect on-time performance. Fares aren’t subsidized by the government—yet they’re typically lower than BART’s because of efficiency. Money goes to customer satisfaction, not excessive compensation.

The Independent Institute notes that competition forces better service at competitive prices. BART faces no such pressure. It can threaten station closures because it knows voters have no alternative—ride the grift train or lose transit entirely.

Who Benefits from the ‘Crisis’

There are clear winners in this expansion of budget without accountability: labor-dominated board members who protect union contracts that haven’t been renegotiated since 2013. Executive management drawing generous salaries while ridership collapses. Unions with gold-plated compensation packages locked in before COVID. Transit activists and nonprofits who lobby for more funds without demanding reform.

This coalition benefits from perpetual crisis. Each bailout cycle preserves their arrangement. Reform would disrupt it.

What Reform Actually Looks Like

Before any tax vote, voters should demand:

- Renegotiate 2013-era labor contracts immediately. The ridership that justified those deals is gone.

- Full overtime transparency. Accessible data, not freeform comment fields the IG can’t access.

- Empower the BART Inspector General with real enforcement powers. No more vetoes at BART’s behest.

- Require fare enforcement as a condition of any new funding. 80% of criminals didn’t pay a fare.

- No new taxes until structural reforms are implemented and verified.

- A fully independent transportation Inspector General office that reports to the 5 county transportation authorities and covers all 27 transportation agencies in the Bay Area.

The Choice in November

A regional tax measure is coming to the ballot in five counties—Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara. It requires majority approval across all five. BART is framing it as “save transit” versus “doomsday.”

That’s a lie. The real choice is whether to reward mismanagement or demand reform first.

BART has proven one thing definitively in 2025: when they prioritize safety over politics, crime plummets and riders return. Nearly 5 million more trips. That’s the path forward—not threatening station closures to extort more taxes.

Fix the overtime grift. Renegotiate the gold-plated contracts. Empower the watchdogs you’ve been obstructing. Stop paying janitors $271,000 to hide in closets.

Then—and only then—come ask voters for help.

We want a functioning and vibrant transit system. More funding should happen but only after the obvious mistakes in operational accountability are undone. If you pour more money into a broken system, you are liable to make the system more broken. And that’s something we have got to stop doing in the Bay Area.

__

Thanks to Debora Allen for reading drafts of this.

Related Links

-

Crime on BART drops 41% in 2025 (Antioch Herald)

-

Crime, Grime, and Greed at BART: Policy Report (Independent Institute)

Comments (1)

Sign in to join the conversation.

I want to clarify something here. I want BART and transit to thrive. I want to support the new measure and fund BART to expand and be a better service. I think the people should hold BART accountable. It is possible to hold two competing ideas in your head and get the best possible outcome. Sometimes, and especially in this case, I think this is the only way you can get the best possible outcome.