We Used to Build Things. What Happened?

From the Panama Canal to parklet regulations—why it’s time for Americans to reclaim technology, growth, and the abundance that once defined it.

The old progressive vision: dams, power lines, and rockets. Teddy Roosevelt built the Panama Canal. FDR electrified the Tennessee Valley. JFK reached the Moon. But then progressive became anti-progress. Image: @jasoncrawford

Source: x.com

The old progressive vision: dams, power lines, and rockets. Teddy Roosevelt built the Panama Canal. FDR electrified the Tennessee Valley. JFK reached the Moon. But then progressive became anti-progress. Image: @jasoncrawford

Source: x.com

TL;DR

America built the Panama Canal, electrified rural America, and put a man on the Moon, but now has become a country of no. It’s time for us to become builders again.

We want abundance and progress—which is all about growth. But the dominant frame is anti-tech and anti-science, a total zero-sum mentality.

Archived tweetWe want abundance and progress which is all about growth But the dominant frame is anti tech and anti science, a total zero sum mentality https://t.co/qM1n5Kn9Py [Quoting @jasoncrawford]: Progressives used to believe in progress. The old left was not just the party of science—it was a party of science, technology & growth. Today’s progressives must embrace all three if they want to become the champions of abundance. My message to the left: https://t.co/2hipgfRTl8 https://t.co/UViv26MWy7

Garry Tan @garrytan February 03, 2026

Jason Crawford’s message cuts to the heart of it: progressives used to believe in progress. Teddy Roosevelt built the Panama Canal. FDR electrified the Tennessee Valley. JFK put a man on the Moon. Then something broke.

When Progressives Stood for Progress

Crawford’s historical case is devastating. The Panama Canal wasn’t just infrastructure—it was celebrated as the “13th Labor of Hercules.” FDR’s Tennessee Valley Authority brought electricity to an entire region that had none. And when JFK called for landing on the Moon, he framed it in the grand story of human progress itself—invoking that narrative to inspire the nation and justify the ambition.

The Moon landing in 1969 was literally the highest America had ever reached. Crawford calls it “a peak moment for America.” But after that, something changed. The America that built dams, highways, and rockets became the country that builds none of it.

The Anti-Growth Turn

The children of the ‘60s saw technology as responsible for pollution, machine guns, chemical weapons, and the atomic bomb. Fair enough—those are real concerns. But instead of being anti-pollution and anti-war, they became anti-technology and anti-growth wholesale.

The Niskanen Center calls it “vetocracy”—so many veto points have accumulated that nothing can get built. NEPA environmental impact statements have grown from a few dozen pages in 1970 to an average of 1,703 pages today. The left’s response to centralized power created a hydra-headed system where any project can be killed by anyone with a lawyer.

The Scarcity Mindset Has Made Everything Worse

Derek Thompson’s epiphany came waiting for a COVID test in freezing DC weather. The pandemic was “scarcity after scarcity"—first no PPE, then no vaccines, then no tests. He zoomed out and saw the pattern everywhere: housing shortages, energy bottlenecks, supply chain crises. What he calls "the abundance agenda” emerged from recognizing that America’s problems aren’t mysterious—we simply stopped building.

Crawford nails the consequence: without growth, people feel they’re playing a zero-sum game. “No, you can’t move to my neighborhood, it’s too crowded.” “No, you can’t immigrate, you’re going to steal my job.” Compare that to abundance thinking: “Yes, move to my neighborhood—we’ll build more homes!” “Yes, immigrate here—there’s so much work to be done, we need all the help we can get.”

From 1900 to 1904, New York City built and opened 28 subway stations. One hundred years later, the city needed about 17 years to build just 3 new stations along Second Avenue. That’s not a decline in engineering capability. It’s a decline in the ability to say yes.

Cost Disease Socialism: Subsidize Demand, Restrict Supply

The traditional socialist call to “seize the means of production” has become something more modest and more myopic: “subsidize my cost of living.” The Niskanen Center coined the term “cost disease socialism” to describe what happens when you pump demand-side subsidies into supply-constrained markets.

Ezra Klein put it simply in his call for supply-side progressivism: if you send housing vouchers into a system with constrained housing supply, macroeconomics dictates that prices can only go up. You’re putting more demand into a system with less supply. Liberalism should think about the supply side too—like actually building houses.

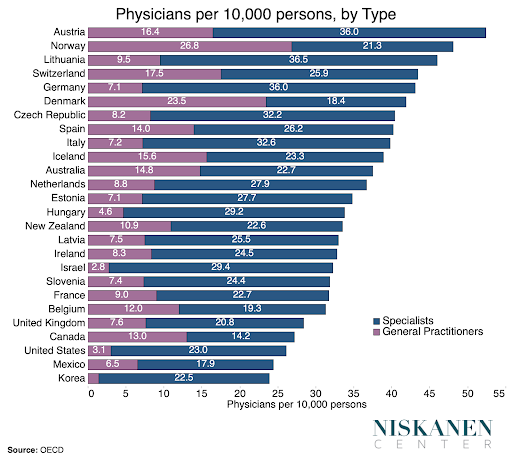

The doctor shortage is the same story. In 1980, Congress took the penny-wise, pound-foolish decision to cap medical residency slots. The result: only about 5 general practitioners per 10,000 Americans, compared to 28.8 in Norway. And just like with housing and energy, we chose to ration supply and subsidize demand and wonder why everything ends up becoming so expensive and increasingly inaccessible.

The Parklet Problem: Good Intentions, Terrible Outcomes

During COVID, San Francisco allowed restaurants to create parklets—outdoor dining in former parking spaces. Everyone loved them. When officials tried to make them permanent, 8 pages of regulations became 60 pages.

The fire department worried about access. Disability advocates noted problems. The Transportation Authority complained about lost parking revenue. Most parklets became illegal under the “improved” regulations. This is blue state governance in miniature: every constituency gets its veto, and the thing that worked gets killed.

Klein calls it “everything-bagel liberalism”—loading every progressive priority onto every project until nothing can move. California spent billions on high-speed rail with nothing to show. China built over 23,000 miles of high-speed rail in the same period. The difference isn’t engineering talent. It’s whether you let people build.

Vetocracy is non-partisan

This isn’t just a left‑wing problem or a right‑wing problem. It’s what happens when every organized interest gets a veto and no one is responsible for actually delivering. The culture war loves to turn every question about housing, energy, or science into a tribal fight, but the real divide is simpler: people who are willing to build the future, and people who are comfortable blocking it.

Yglesias makes the key point: not everything needs to be partisan warfare. These are really questions of special interest politics. When you inject them into culture war frames, it becomes hard to make progress. “The left can still be the party of abundance,” Crawford writes, “if it wants to be.”

But it won’t be easy. It will be uncomfortable. Because becoming the party of abundance requires truly embracing technology and growth—and America has developed an allergic reaction to those things.

Abundance Thinking: Yes, We Can Build More

Noah Smith identifies four things America needs in abundance: housing, energy, healthcare, and dignity. America hit the limits of cheap suburban sprawl in 2006. The knowledge economy clusters workers in expensive cities where landlords capture the value they create.

YIMBY is abundance made local: more homes means lower rents, shorter commutes, higher birthrates, bigger talent pools—everything a growth economy needs. Yglesias distinguishes between “affordable housing” (a niche term for subsidized units that a lucky few get) and actual abundance: market prices everyone can afford because there are enough houses.

Thompson and Klein’s new book Abundance argues this could become America’s next political order—not left or right, but the party that builds versus the party that blocks. The Niskanen Center notes that Klein and Thompson are offering “not just discrete policy ideas, but a new organizing principle for progressive politics.”

Our politicans still run on scarcity scripts even as technology makes true abundance possible in more and more places. What’s happening right now, in AI, in energy, in materials, in biology, is the shift from allocation to creation. The real choice in front of us is simple: we can keep saying ‘no’ and let others decide the future for us, or we can remember that we are the people who build—and choose to lead the age of abundance.

Teddy Roosevelt didn’t file environmental impact statements for the Panama Canal. FDR didn’t let 60 pages of regulations stop the TVA. JFK didn’t wait for consensus to reach the Moon.

We know abundance is possible, because we’ve built it before and we’re building it in pockets right now. The question isn’t whether it can be done—it’s whether we are willing to pick up the mantle again. If we decide that Americans are once more the people who say yes to science, yes to technology, and yes to growth, then we can make this the next great age of building. The only real question left is how quickly we choose to start.

Related Links

-

Progress for Progressives (@jasoncrawford)

-

The Abundance Agenda (The Atlantic)

-

Supply-Side Progressivism (New York Times)

-

Cost Disease Socialism (Niskanen Center)

-

Abundance and the Permanent Problem (Niskanen Center)

-

A Grand Bargain for Permitting Reform (Institute for Progress)

-

The Politics of Abundance (Slow Boring)

Comments (0)

Sign in to join the conversation.